MAY 9 — Power comes in many guises. As political anthropologist James Scott insightfully argued, even the seemingly powerless are not wholly devoid of agency. Power is not merely the domain of tanks and treaties—it is also about influence: the ability to affect outcomes, shape preferences, and steer decisions, even subtly, without force. In this regard, the work of Professor Joseph Nye, who passed away recently at the age of 88, has never been more relevant.

Nye, a titan in the field of international relations, gave the world a language to describe non-coercive forms of influence. His term, soft power, has since become a staple in both academic and policy circles, though few wield it with the nuance and intellectual clarity Nye brought to bear. As the global order experiences new forms of fragmentation, and as American leadership is increasingly questioned, the world mourns not only the loss of a great thinker — but also the loss of one of the last architects of a more optimistic, cooperative international order.

Nye’s academic career took flight in the early 1970s. Alongside fellow scholar Robert Keohane, he co-authored Power and Interdependence (1977), a foundational text in international political economy. Their concept of complex interdependence broke with the realist orthodoxy that dominated Cold War thinking. Rather than seeing states as isolated actors pursuing zero-sum interests, Nye and Keohane emphasized the dense webs of economic, political, and institutional connections that made war among developed powers increasingly costly and irrational. This was, in essence, a revival of liberal internationalist thought — what some scholars later termed commercial liberalism.

But Nye’s most impactful contribution emerged in 1991, with the publication of his book Bound to Lead: The Changing Nature of American Power. At the time, Paul Kennedy, a British-born historian at Yale, had shaken the American strategic community with his thesis of “imperial overstretch.” Kennedy warned that the United States, like previous empires, was burdening itself with unsustainable military commitments. Nye challenged this view head-on. He argued that the US was not in decline, but rather in a unique position to lead the world through its capacity to attract rather than coerce.

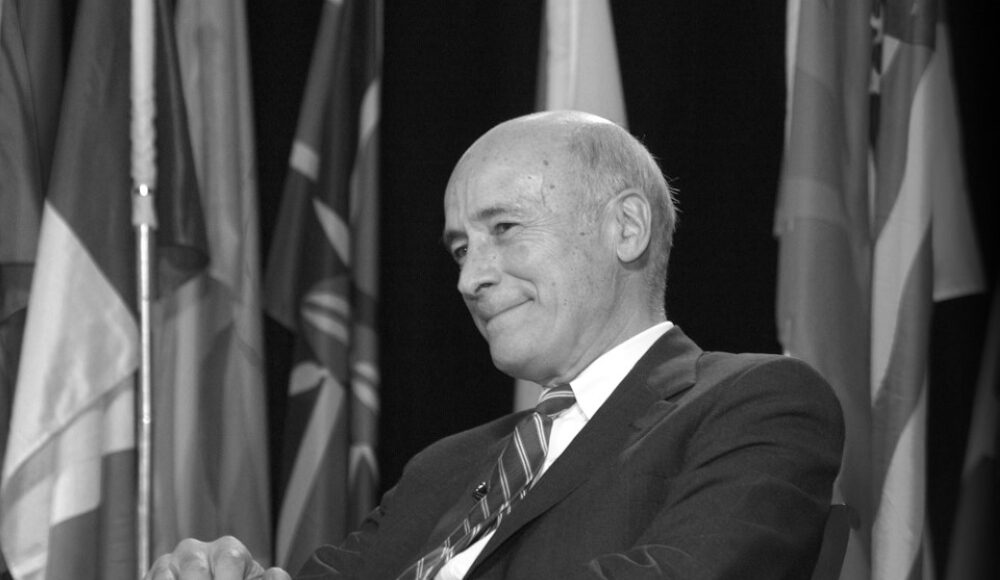

Joseph Nye coined the term ‘soft power’ and advised multiple presidents. — Picture via Facebook/Harvard Kennedy School

Soft power, as Nye conceptualized it, was not about manipulation. It was about admiration. When other nations or peoples adopt your values, emulate your institutions, or seek to be associated with your way of life, they are being influenced — not because they are compelled, but because they are inspired. American democracy, popular culture, technological innovation, and educational institutions served as examples of this appeal. In a post-Cold War world, soft power offered a new strategic grammar — one rooted in the power of ideas, culture, and legitimacy.

The fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, followed by the dissolution of the Soviet Union, gave credence to Nye’s optimistic vision. What Charles Krauthammer famously described as the “unipolar moment” was not only defined by overwhelming US military dominance but also by the widespread adoption of American-style governance and markets. For a time, it seemed as though the American model had won.

Yet Nye was also clear-eyed about the limits of soft power. In his later writings — most notably Soft Power: The Means to Success in World Politics (2004) — he emphasised that influence built on attraction must not be tainted by what he called the “three Cs”: coercion, corruption, and co-optation. If any of these are involved, the power ceases to be “soft” and becomes something more insidious. This moral dimension is what set Nye apart. He did not merely seek to describe international behaviour; he sought to provide a framework for ethical leadership.

Nye also remained committed to policy impact. As Dean of Harvard’s Kennedy School and later as Assistant Secretary of Defense under President Clinton, he worked to combine soft and hard power into what he termed smart power — a strategy that leverages both attraction and strength in appropriate balance. Together with his former colleague Richard Armitage at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), Nye advocated for a pragmatic and principled US foreign policy grounded in legitimacy and alliances.

Tragically, both Nye and Armitage passed away within weeks of each other. Their deaths come at a time when the United States appears to be moving away from their vision. Under President Donald Trump, now the 47th President of the United States, America’s role as a convener, moral leader, and institutional anchor has eroded. What Nye called “convenor power” — the ability to rally diverse actors toward common solutions — has diminished. In its place is a more transactional and confrontational posture, one that mistakes volume for vision.

The irony is striking. Nye passed away at a moment when his ideas are most needed. The world is increasingly sceptical of American benevolence. The credibility of the US as a democratic beacon and global leader has been called into question, not just by adversaries but by long-time allies.

Yet perhaps that is precisely why his legacy matters more than ever. Nye taught us that true leadership rests not on dominance, but on trust and persuasion. In a fragmented world longing for cooperation, his vision of soft — and smart — power remains a guiding light.

* Phar Kim Beng, Professor of Asean Studies at IIUM, was a former Head Teaching Fellow of Historical Studies HS 12 originally pioneered by Professor Joseph Nye and Stanley Hoffmann. HS 12 is a major part of the Core Curriculum of Harvard on “World History from 15th century to Post Cold War.”

** This is the personal opinion of the writer or publication and does not necessarily represent the views of Malay Mail.