KUALA LUMPUR, May 28 — In an era marked by intensifying geopolitical rivalries, global economic fragmentation, and technological decoupling, the recently concluded Asean-GCC-China Economic Summit in Kuala Lumpur was more than just another multilateral gathering.

It was, in effect, a sophisticated and subtle rehearsal — a trial effort to envision a new global platform of mutual respect, shared development, and inclusive diplomacy.

To allow leaders and decision makers to form a camaraderie.

A sense of collegiality.

Yet, to truly understand the Summit’s significance, one must go beyond its surface-level formalities, invariably, to parse the deeper institutional and civilisational undercurrents that shaped it.

These summits clearly had the underpinnings of the Islamic world from GCC, the archipelagic support from Malaysia, Singapore and Indonesia, and the Confucian backing of China, Vietnam and other communities that see themselves as part of this identity marker in East Asia.

The KL Declaration: Not a beginning, but a continuation

While the “Kuala Lumpur Declaration on Asean 2045: A Shared Future”, going into 150 pages, is the anchor of this Summit, it did not emerge in isolation.

It stands as a continuation of a decade-long journey that began with the Kuala Lumpur Declaration on “Asean 2025: Forging Ahead Together (agreed in 2015),” through to the “Ha Noi Declaration on Asean Community’s Post-2025 Vision (agreed in 2020),” and was strengthened further by the “Asean Connectivity Post-2025 Agenda,” (agreed in Phnom Penh, 2022) and the “Labuan Bajo Declaration (agreed in 2023),” as well as the “Vientiane Strategic Plans” (agreed 2024).

Each of these milestones represents institutional memory and policy continuity, driven by Asean’s determination to evolve as a rules-based, people-oriented, economically competitive region based on cross sectoral and cross pillar collaboration.

Thus Asean will always have Political Security Community, the Economic Community and the Social Cultural Community.

Of the three, Asean is strongest in the first, although the second and third community are always encouraged to shape up.

This is why Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim suggested the inclusion of GCC and China, without leaving out the option for another Plus 1 or Plus 3 options to meet with Asean.

For example, the invitation to have the US Asean Summit as and when the Trump Administration is ready as Anwar explained on May 26 is an open one.

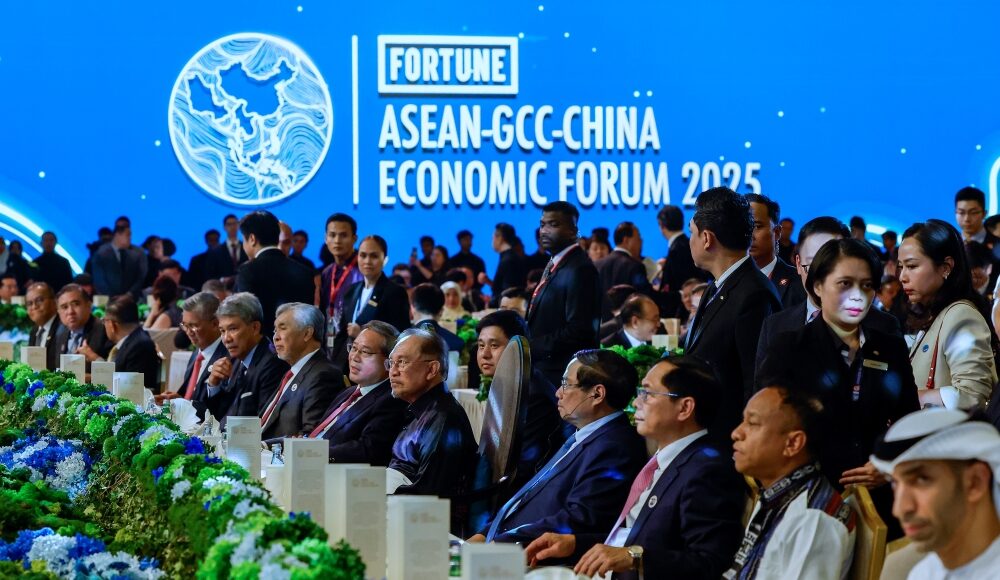

Prime Minister Datuk Seri Anwar Ibrahim seen during the Asean-Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC)-China Economic Forum 2025 in Kuala Lumpur last night. — Bernama pic

Join the special summit as and when the US is ready.

The same applies to all ten Strategic Dialogue Partners of Asean, indeed, Sectoral and Development Partners too.

Even the UN can have a Special Summit with Asean.

In this sense, there has been a paradigm shift in Kuala Lumpur.

The KL Declaration thus offers a vision of a sustainable, connected, resilient, and innovative Asean, rooted in a shared past and oriented toward a pragmatic future.

GCC’s aspirations: From the 7th partner to the top three

For the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) — comprising Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Qatar, Bahrain, Kuwait, and Oman — the summit was an opportunity to recalibrate its global economic engagement.

Currently ranked as Asean’s 7th largest trading partner, the GCC’s ambition is clear: to become one of Asean’s top three trade partners within the next two decades.

If this is not the explicit ambition of GCC, they ought to think in these terms since Anwar correctly affirmed Asean is the most peaceful regions in the world, at a time marked by serious geo-political and geo-economic turbulence.

To be sure, such an aspiration is not merely symbolic.

The GCC states are actively diversifying away from their historical reliance on hydrocarbons.

Vision plans such as Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030, Qatar National Vision 2030, and the UAE’s We the UAE 2031, all share a common goal — economic transformation through logistics, green technology, digital finance, education, and sustainable development.

In Asean, they see a young, dynamic, and high-growth partner with untapped potential.

It was President Prabowo Subianto who affirmed that Indonesia has a young population with an average age of 28–29 in a country with almost 300 million people.

Asean has to learn to be bolder, just as other regional organisations have to do the same to connect with Asean.

Moreover, Asean’s neutrality and flexibility allow GCC sovereign wealth funds to park long-term investments in infrastructure, Halal ecosystems, renewable energy, and smart city development — all without entanglement in ideological blocs or proxy conflicts.

The Summit’s subtext was clear: the GCC is pivoting eastwards, and Asean stands ready to welcome that realignment.

Defence and security: Building trust through education

Although security and defence cooperation were not the main agenda, they were certainly present — in quiet but meaningful ways.

Instead of showcasing military alliances or joint drills, Asean and the GCC are prioritising defence education and strategic literacy.

Foremost of which, in the view of Anwar, is the absence of any “tilt towards China.”

Asean remains receptive to open regionalism.

Meanwhile, hidden somewhere in the documents attest to the importance of National Defence Universities across both regions.

All are beginning to collaborate on curriculum development, cyber security dialogues, and strategic studies programmes.

Rather than military manoeuvres, it is defence diplomacy through education that underpins this aspect of cooperation.

This reflects Asean’s broader security philosophy: non-alignment through institutional engagement.

It builds trust incrementally, preparing both regions for cooperative responses to shared threats like terrorism, maritime piracy, pandemics, and digital warfare — without triggering geopolitical alarm bells.

China’s presence: Strategic patience and embedded interests

China’s involvement in the summit was subtle but significant.

While the format carefully avoided turning the event into a geopolitical declaration, China’s role as a facilitator of infrastructure such as Asean Power Grid, digital connectivity, and trade integration was undeniable.

Through initiatives like the Digital Silk Road, Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), and Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), China has deeply embedded itself in Asean’s growth engines.

So is Japan and South Korea as and when their roles become more prominent in the East Asian Summit in October 2025, again in Kuala Lumpur.

At the same time, China has become a leading partner to several GCC states, particularly in energy, telecommunications, and AI research.

Yet, the architecture of the Summit deliberately avoided overemphasis on China too.

There was no binding communiqué, no formal pact, and no new alliance structure.

This was intentional.

The goal was to craft a suggestive, not declarative platform — an inclusive space where all parties, including the United States and the European Union, could be engaged on Asean’s terms.

Malaysia’s quiet leadership: Steering Asean through subtle statecraft

Malaysia’s Chairmanship of Asean in 2025, under Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim, has demonstrated a form of leadership rooted in consensus-building and economic statecraft.

Unlike more performative or overtly ideological leadership styles, Malaysia’s approach has been calculated, cautious and constructive.

Rather than using the Chairmanship to attack or isolate other powers, Malaysia used it to showcase Asean’s relevance.

The Summit also sets the stage for the East Asia Summit (October 2025) and future digital frameworks, such as the Asean Digital Economy Framework Agreement (Defa).

Moreover, Anwar’s vision includes the proposal of an Asean-US Special Summit without preconditions to address rising tariffs and trade frictions, ensuring that Asean remains engaged with all partners — East and West, developed and developing.

The real story: From summits to systems

The real success of the Asean-GCC-China Summit lies not in the headlines, but in the institutional scaffolding it reinforces.

It is a rehearsal of trust, an opening act in civilisational diplomacy, and a signal that Asean is not merely reacting to global currents, but shaping them.

We are witnessing not a pivot to China, nor a tilt to the Gulf, but a strategic triangulation — one that allows all three actors to secure their interests through mutual respect and multilateral rules.

In a world plagued by distrust, polarisation, and ideological rigidity, the Asean-GCC-China Summit offers a different model — a quiet geometry of cooperation, where process matters more than posture, and where the future is negotiated, not imposed.

Asean, long derided as weak or indecisive, may have just reminded the world that its strength lies in its subtlety.

It doesn’t need to shout to be heard.

It just needs to convene — and let others come to the table.

* Phar Kim Beng, PhD, is Professor of Asean Studies at the International Islamic University Malaysia and Visiting Faculty, Asia-Europe Institute, University of Malaya.

** This is the personal opinion of the writer or publication and does not necessarily represent the views of Malay Mail.