MAY 31 — In a recent and poignant Time article, economist Richard S Grossman reminds us that when political leaders ignore economists and elevate personal pride over empirical analysis, economic catastrophe is not a possibility — it is a pattern.

Grossman draws sharp historical comparisons: President Andrew Jackson’s assault on America’s nascent central bank and Winston Churchill’s ill-fated return to the gold standard.

Both decisions were rooted in ideological conviction and personal pride, not evidence or consensus.

Now, in the second term of Donald J Trump, history threatens to repeat itself — only this time, on a global scale. Trump’s self-referential style of governance risks destabilising not just the US economy but the very foundations of global economic interdependence.

His actions echo Jackson and Churchill — but they are also amplified by a kind of hubris unique to this media-saturated age, where policy is shaped more by image than substance, by ego rather than expertise.

Jackson’s Bank War: Populism at the expense of stability

In the early 1830s, President Andrew Jackson waged war against the Second Bank of the United States. Chartered in 1816, the Bank had functioned as a quasi-central institution, restraining inflation and regulating credit. Jackson, however, viewed it as a tool of elite corruption and vetoed its recharter in 1832, allowing it to collapse by 1836.

His Specie Circular of 1836, which mandated payment for government land in gold or silver, drained the economy of liquidity and triggered the Panic of 1837.

As chronicled by economic historian Peter Temin, this crisis caused GDP to contract by up to 30 per cent, and unemployment skyrocketed. It took nearly a decade for the economy to recover.

Jackson’s decision, made in defiance of economic logic, delivered a populist victory — and a national calamity.

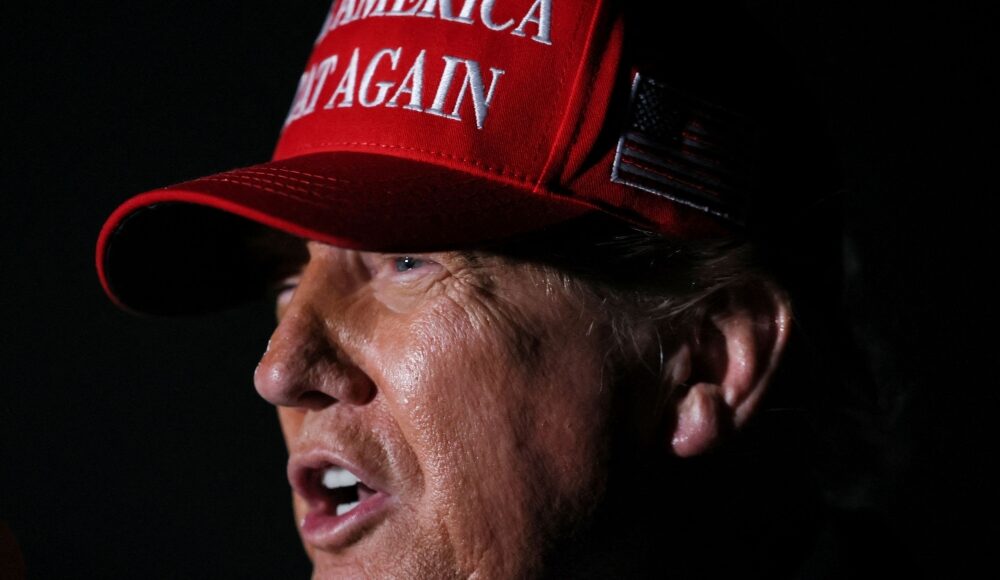

US President Donald Trump speaks with the media after a trip to Pennsylvania, at Joint Base Andrews, Maryland, US May 30, 2025. — Reuters pic

Churchill’s gold standard gambit: Pride in decline

Fast forward to 1925. Winston Churchill, then Chancellor of the Exchequer, committed Britain to returning to the gold standard at its pre-World War I parity — despite explicit warnings from economists like John Maynard Keynes.

The move drastically overvalued the pound, making British exports uncompetitive and forcing deflationary wage cuts across industry.

The economic damage was severe. Between 1921 and 1929, while the United States and France saw GDP gains of 40–50 per cent, Britain lagged behind with under 20 per cent. The North of England sank into chronic unemployment.

The General Strike of 1926 and other labour uprisings signalled deep unrest. Churchill, clinging to imperial nostalgia and fiscal orthodoxy, stayed the course until 1931 — when a full-blown crisis forced Britain off the gold standard.

Trump’s economic nationalism: Narcissism over institutions

Trump’s second term is shaping up to be a repetition of these self-inflicted traumas. But while Jackson and Churchill made costly decisions for their nations, Trump’s impact is transnational.

His economic worldview is transactional, driven by an obsession with trade deficits and a conviction that tariffs will restore American greatness.

This belief contradicts decades of economic research. Trade deficits are not inherently harmful, nor do tariffs reduce them. They tend to raise prices for consumers and provoke retaliatory measures from trading partners.

Yet Trump persists, seemingly convinced that personal instincts are superior to expert counsel.

He routinely undermines institutions like the Federal Reserve, publicly attacks international economic bodies such as the WTO, and treats trade as a zero-sum game.

His policies, lacking in consistency and long-term logic, have already begun to erode global trust in American reliability — both as a trade partner and as a steward of global finance.

From trade policy to global shockwave

The world’s largest economy cannot afford this kind of unpredictability. In contrast to Jackson and Churchill — whose economic errors had localised effects — Trump’s decisions ripple through complex global supply chains, rattle markets, and stoke geopolitical tensions.

His tariff wars have hit not just China but also traditional allies like the European Union, Canada, and Japan.

The result? A deeply fragmented global trade environment. Allies no longer assume continuity in American policy. Investment flows hesitate.

Emerging markets, many of them reliant on exports, suffer. Trump’s economic strategy — fuelled by bravado and nostalgia — is incompatible with the integrated global system the US itself helped create.

The theatre of strength, the reality of retreat

Richard S Grossman rightly points out that Trump’s view of tariffs is rooted in a misunderstanding of history. He romanticises the 19th-century Gilded Age, a time of high tariffs, while overlooking its accompanying instability, monopolism, and deep inequality.

Trump’s policies risk bringing back that era — not as triumph, but as cautionary tale.

What truly binds Jackson, Churchill, and Trump is not simply error, but ego — the conviction that personal willpower can override economic complexity.

But in Trump’s case, this ego is magnified by media spectacle and a disdain for dissent. His economic policy is crafted not through consultation or deliberation, but through impulse.

The coming hammer blow

The most dangerous consequence of Trump’s economic hubris is not just stagflation or market volatility — it is the collapse of global trust. Trust is the glue of the international economic system.

When nations can no longer rely on US commitments, the temptation grows to seek alternatives — whether in digital currencies, alternative trade blocs, or parallel security arrangements.

This erosion of trust could mark the twilight of US economic leadership. While the dollar remains dominant and American markets deep, overreach can accelerate decline.

The American century — once built on openness, innovation, and stable leadership — now risks ending in retreat, with tariffs not as tools of power but as symbols of decline.

Trump’s economic nationalism, then, is not just policy. It is performance.

And like all performances, it ends.

The question is whether the final curtain will fall on American economic primacy — or whether institutions, allies, and economists can intervene in time to prevent the hammer blow from becoming permanent.

* Phar Kim Beng, PhD, is professor of Asean studies at the International Islamic University Malaysia.

** This is the personal opinion of the writer or publication and does not necessarily represent the views of Malay Mail.