KUALA LUMPUR, April 15 — When you see headlines warning that Malaysia will need to recycle 870,000 electric vehicle (EV) batteries by 2050, it’s easy to feel alarmed. The number, cited in a recent Malay Mail article, suggests a looming waste crisis from EV adoption. But is that really the case? Or are we applying outdated assumptions to a fast-evolving technology?

And while I agree with the overall goal — Malaysia absolutely needs to build up its battery recycling ecosystem — some of the projections may overlook important developments in battery longevity, second-life use cases, and the evolving role of recycling in an established circular economy.

Let’s unpack a few of the claims.

Claim 1: EV batteries typically last eight to 10 years

Most modern EV batteries are designed to last far longer, with current chemistries like lithium iron phosphate (LFP) rated for up to 3,500 charge cycles.

Battery lifespan depends on several factors: chemistry, cooling, usage patterns, and software management. Newer EVs using LFP batteries can last up to 3,500 full charge cycles. Assuming a conservative 250km per charge, that’s nearly 875,000km of driving. Even nickel manganese cobalt (NMC) batteries used in many performance EVs can see 1,000 to 2,000 cycles — or around eight to 10 years before capacity drops below 80 per cent.

The BMW iX battery. — SoyaCincau pic

More importantly, a degraded battery is not a dead battery. There is the potential for module-level repair, where only the faulty part of a battery pack is replaced. This can significantly extend the usable life of the battery without needing full recycling. If repairability becomes standard practice, the number of batteries requiring full recycling by 2050 could be much lower than projected.

In Malaysia, the average annual driving mileage is around 20,000km. So theoretically, a well-maintained EV battery can last over 15 years, especially with EVs now having better battery cooling systems and battery management software.

Case studies:

- First-gen Nissan Leaf and Renault Zoe — some of the earliest EVs on Malaysian roads — are still operating today with battery replacements only in extreme degradation cases.

- Tesla Model 3 LFP batteries are expected to last well over 500,000km with minimal degradation.

- The Aegis Blade battery developed by Geely and used in the Proton e.Mas 7 is known for its robustness, tested under extreme heat and puncture scenarios, and supports over 3,500 charge cycles.

The first-gen Nissan Leaf (right) launched in 2013, is still running in Malaysia. — SoyaCincau pic

The real-world data suggests longevity is improving, not getting worse.

Claim 2: 870,000 batteries to be recycled by 2050

We couldn’t verify where this number comes from. Is it based on all EVs currently on the road? Projected future sales? Does it include hybrid and plug-in hybrid vehicles? What about electric motorcycles?

But here’s a bigger issue: this figure likely assumes a linear replacement model — i.e., that every battery sold will eventually be disposed of and recycled.

That ignores a few important factors:

- Second-life applications: EV batteries with 70 to 80 per cent state of health are often repurposed for battery energy storage systems (BESS), especially for solar power or grid backup.

- Battery repairability: More EV makers now design batteries to be serviceable. You don’t need to replace the entire pack — just a few modules.

- Battery-as-a-service models: Some manufacturers like Nio offer swappable battery tech, which makes repair and lifecycle management much more efficient.

Even when an EV battery is no longer optimal for driving, it often retains 70 to 80 per cent of its original capacity — still plenty useful for less demanding applications. This opens the door for stationary storage such as:

- Residential solar backup systems

- Grid-balancing storage for utilities

- Backup power for commercial buildings

- Nissan, for example, has repurposed used Leaf batteries to power streetlights in Japan. Other companies globally are using second-life EV batteries for modular storage units in renewable energy setups.

This approach aligns with the “Reduce, Reuse, Recycle” hierarchy under the Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) framework — reuse comes before recycling, forming part of the environmental pillar of sustainable development.

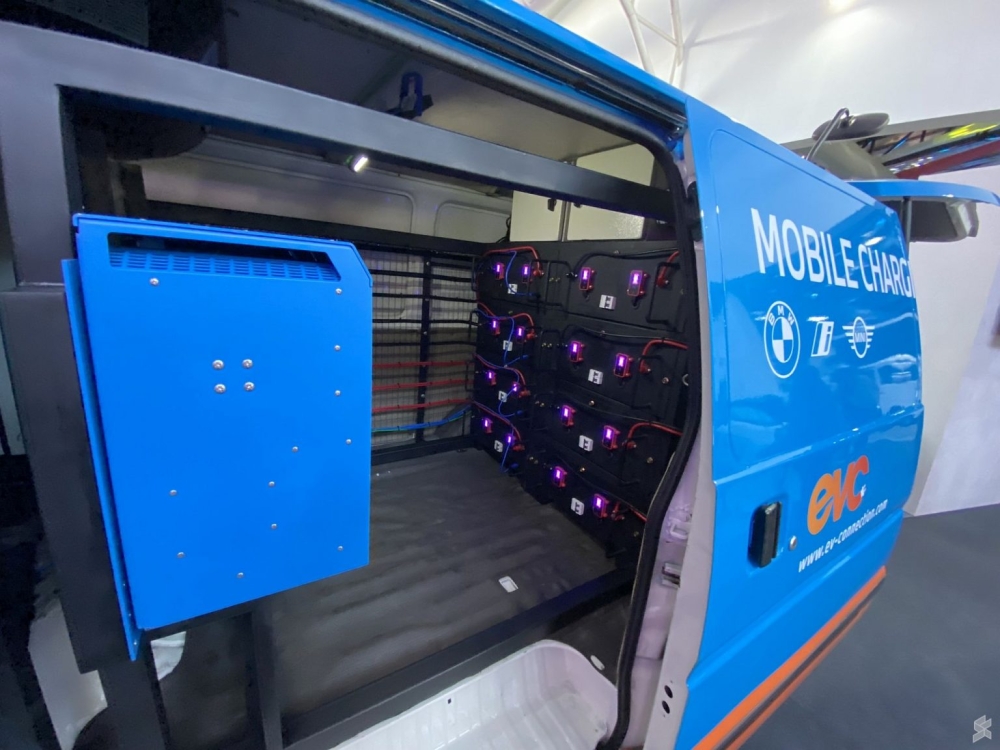

BMW and EVC’s Mobile Charging Vehicle uses repurposed EV batteries. — SoyaCincau pic

These second-life solutions help extend battery value, reduce demand for new raw materials, and lower the energy footprint associated with recycling processes.

What other countries are doing

Countries with mature EV markets are already building frameworks for battery circularity:

- European Union: The EU Battery Regulation requires manufacturers to design batteries for disassembly and mandates recycling targets. Producers are also responsible for collecting and reusing battery materials.

- China:

- Introduced Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) requiring manufacturers to manage battery disposal.

- Has a national goal to recycle 70 per cent of EV batteries by 2030.

- Japan: Beyond streetlights, Japan’s automakers have led battery collection and reuse programmes in partnership with municipal councils.

- United States: The Bipartisan Infrastructure Law allocates over US$3 billion for battery material recycling and second-life research.

These models prioritise repair, repurposing, and regulated recycling in that order. Malaysia can adapt these practices to fit our own context.

NMC Battery Module for Porsche Taycan. — SoyaCincau pic

Recycling still matters — but it’s not the first step

Let’s be clear — recycling is an essential part of a circular EV ecosystem. Valuable materials like lithium, cobalt, and nickel should be recovered and reused to reduce reliance on mining. But recycling should not be treated as the first or only option.

The concern is that if Malaysia positions itself purely as a recycling hub without developing local EV battery manufacturing, we risk becoming a dumping ground for used batteries. Instead, we need an integrated strategy that supports:

- Battery repair and diagnostics

- Second-life repurposing industries

- Domestic battery production (even for non-EV use like solar)

- Clear regulations and incentives

Only then can we truly close the loop.

Final thoughts

As EV adoption scales, the spotlight on battery waste will only intensify. But let’s not jump the gun. Malaysia has the opportunity to design a circular battery ecosystem that’s future-proof, economically beneficial, and environmentally sound. Let’s not just prepare to recycle 870,000 batteries — let’s work to reduce that number through smart policies, better technology, and a rethink of how we define waste. — SoyaCincau