SAO PAULO, May 18 — Cintia Bomfim saw her eldest son struck twice by rubber bullets from police during protests this week in Moinho, downtown Sao Paulo’s last favela, which is about to make way for a park and train station.

Then on Thursday, after a days-long standoff between authorities and residents resisting their ouster, she received news of an agreement to provide free housing for her and hundreds of other families elsewhere in Latin America’s richest and most populated city.

“If I have to leave, I want something better,” Bomfim, a 39-year-old mother of three, told AFP amid an intimidating police deployment to quell protests against the razing of houses already vacated.

Ramshackle as they were, these were the only homes the residents of Moinho could afford.

“I didn’t come to live here because I wanted to: I used to sell candy at a traffic light and couldn’t afford a more expensive rent outside the favela,” said Bomfim.

Cintia Bonfim, resident of Moinho favela, poses after an interview with AFP, during a protest against the state government’s plan to evict them from their community in Sao Paulo downtown May 13, 2025. — AFP pic

She had been living in Moinho for 18 years, and runs a small bakery on the main street, which she will now have to abandon.

Central Sao Paulo, a city of some 12 million people, is a seemingly incongruous mix of trendy bars and restaurants right next to mass low-cost housing, people living on the street, and roaming drug dealers.

In the mix is Moinho, which sprung up in the 1990s between two railway tracks in an area the size of three football fields, and which authorities have long wanted to clear.

It was, until recently, home to about 900 families, of which about a quarter have already left.

Riot police throw tear gas at residents of the Moinho favela during A protest against the state government’s plan to evict them from their community in downtown Sao Paulo, Brazil, on May 13, 2025. — AFP pic

‘Cleansing’

This week, AFP observed military police fire tear gas and rubber bullets and point firearms at protesting residents.

Officers entered some homes with dogs, allegedly in search of drugs and weapons.

The government of Sao Paulo claimed “organised crime” was behind the community resistence — an accusation residents deny.

Moinho is the only favela left in central Sao Paulo after several others were cleared in recent decades, though larger ones remain on the city’s outskirts.

Opponents decry what they see as a “cleansing” of poor people in a process of gentrification to pave the way for real estate speculation.

Sao Paulo is the most expensive state capital of Brazil, with an average rent of 1,700 reais (about RM1,288) for an apartment of 30 square metres, according to the Institute of Economic Research Foundation.

The high housing costs have increased pressure to “expel poor, black and marginalised people,” opposition lawmaker Paula Nunes of Sao Paulo state, told AFP.

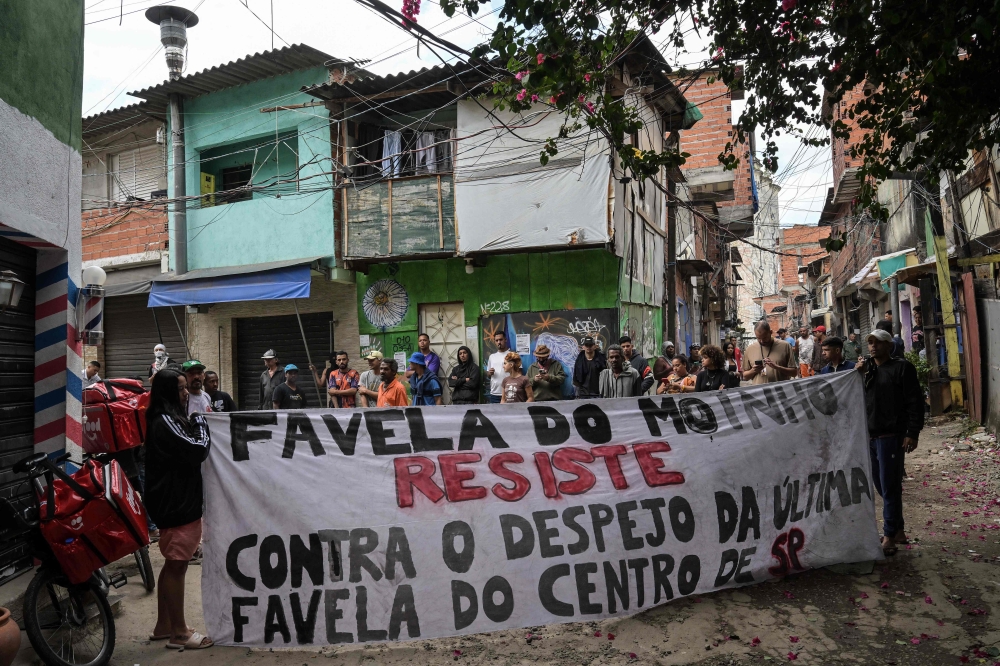

Residents of the Moinho favela protest against the state government’s plan to evict them from their community in downtown Sao Paulo May 13, 2025. — AFP pic

‘Important achievement’

Initially, the state government had offered Moinho residents lines of credit to acquire subsidised housing elsewhere in Sao Paulo. Most of the planned units, however, are not yet ready for occupancy.

In the meantime, residents were supposed to receive 800 reais per month to pay rent elsewhere.

The land on which the favela was built belongs to the national government, which had agreed to transfer it to Sao Paulo on condition that decent alternative housing is found.

This week, the federal government said it would halt that transfer until “a negotiated and transparent eviction process” was agreed on.

Then on Thursday, after days of protests that included the blocking of railway tracks, the national and state governments reached an agreement to jointly finance new housing for Moinho residents — bringing an end to the unrest.

Under the deal, each family would receive 250,000 reais to buy a house.

“The free provision (of housing) is a long-awaited and important achievement,” celebrated Yasmim Moja, a leader of the Moinho residents’ association. — AFP