JULY 10 — They say reading is free, but is it?

In Malaysia, books are expensive, libraries are uneven, and access is shaped by income, infrastructure and class. The cost of being a reader isn’t just measured in ringgit. It’s measured in opportunity, inequality and culture.

How much does a book cost?

You walk into a bookstore in Kuala Lumpur and pick up an imported paperback on statistics — RM60. A historical narrative? RM115. If you’re earning Malaysia’s minimum wage of RM1,700, that’s nearly four to seven per cent of your monthly income. For one book.

That’s your internet bill. Or a week’s worth of lunches.

Books aren’t taxed in Malaysia, but they’re not cheap. Many are imported. That means you’re paying for printing, freight, import duties, logistics, distributor mark-ups and currency exchange. We don’t have a fixed book pricing law, so prices vary across retailers. Discounts are inconsistent, and bookstores may be operating on thin margins.

If you buy books, how likely are you to read?

Buying books can predict whether someone reads — according to a 2023 study by the National Library (PNM). Among those who bought books, 97.2 per cent are more likely to read. Among those who didn’t, only 17.6 per cent read.

Put simply, access fuels reading.

Without the ability to buy or borrow, many might simply stop.

‘For sale in the Indian sub-continent only’

I buy my books in India when I visit family. International publishers print low-cost editions for the sub-continent, so mass-market paperbacks cost a fraction of what we pay here. The same paperback on statistics that costs RM60 here? RM24 in India. The historical narrative at RM115? RM50.

Malaysia, with its smaller market, cannot benefit from the same economies of scale. Our readers pay more and get less.

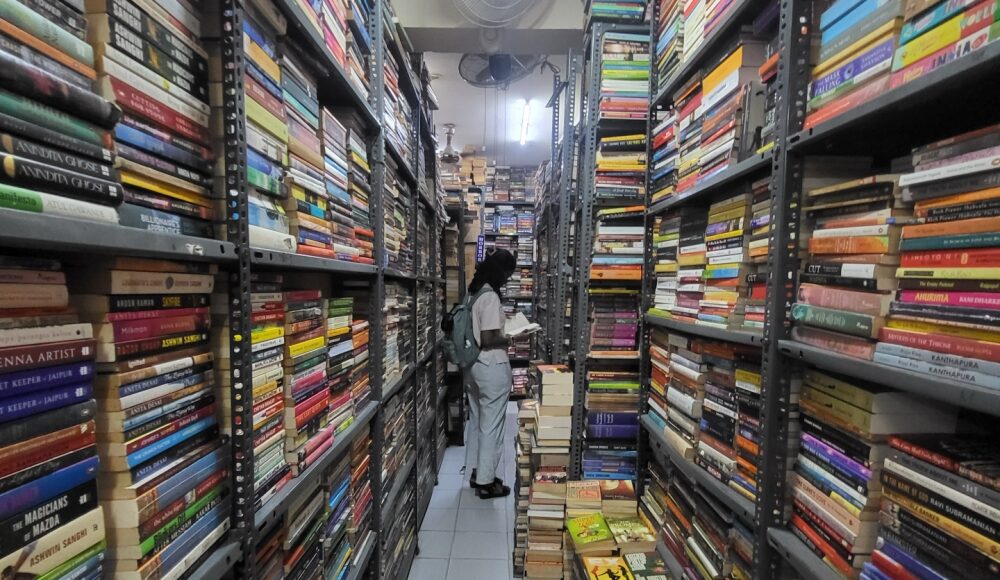

The informal economy of reading

When books are unaffordable, Malaysians find workarounds. We share PDFs. Trade second-hand books. Borrow from friends. Join online book clubs. Scroll through #BookTok, driving the demand for trending titles.

But workarounds are not access. They demand digital literacy, time and community. They leave out those without digital access and time to navigate these channels.

Only 11.1 per cent of Malaysians cite financial constraints as the main barrier to buying reading materials, but nearly 45 per cent of respondents to the PNM study say they get reading materials free, from the library or online. Another 12.2 per cent say they have to prioritise basic needs. Cost shapes access.

The second-hand economy keeps books in circulation — passed from one person to another, long after the first sale. But publishers don’t profit from resales. Digital books and social media-driven sales have opened new doors, but innovation can’t mask the sector’s fragility, with rising printing costs, weak local publishing and few incentives for independent retailers.

We can’t value what we don’t measure

In 2005, Malaysians were reading an average of two books a year. They now read 24 books a year. The infrastructure, though, hasn’t kept up.

The National Book Data Report reveals that the Malaysian book industry is valued at RM6 billion. Yet its share of GDP has declined from 0.5 per cent in 2015 to just 0.38 per cent in 2021.

PNM’s allocations for the purchase of collection materials have been cut. We don’t collect comprehensive data on book pricing.

The data that does exist on pricing and funding is scattered, inconsistent and often inaccessible to the public.

We value the reading ecosystem very little.

The people’s bookstore

We like to say libraries are the solution. They should be, in theory.

As a child, my library card was my first credit card. But as an adult? I stopped going. The libraries I knew were cold, grey and academic. No natural light. No trees outside. Located in busy districts, away from neighbourhoods, and closed on public holidays.

A public good, now a relic of an old model of education. Not part of a modern reading economy.

Malaysia has about 1,431 public libraries, according to PNM. But there isn’t a public map of where they all are. A list, at the very least. Most people don’t know where the nearest one is.

Some branches feel like archives, not community spaces. They tell you to finish your assignments, not to stay and enjoy a book. They’re academic, not recreational.

Reading in a park is recreational.

Just read more?

It isn’t about whether you want to. It’s about whether you can.

If books cost as much as groceries, if libraries are closed when you’re off work, and if the cost at bookstores is out of reach, then the question isn’t why people don’t read. It’s what we’ve done to make it so hard to read.

Reading doesn’t begin with motivation. It begins with access.

Think social determinants — income, geography, language and infrastructure. The conditions that shape whether someone can become, stay and thrive as a reader.

Reimagine libraries and public spaces

I lived in an old Soviet-era apartment block when I studied in Russia. The ground floor of one of the nearby blocks housed a public library — as casually as the bus stop and the grocery store.

Our neighbours in Indonesia are showing what’s possible. Independent libraries are thriving, cared for by individuals and communities. A design firm aims to build 100 community and climate-friendly microlibraries by 2045. Citizen volunteers have set up mobile libraries on boats, pedicabs and trains.

They have understood that it is not a lack of interest, but a lack of access.

So imagine this. Libraries in neighbourhoods. Not the kind filled with leftover donations, but stocked with new titles people actually want to read.

Built in partnership with state libraries and publishers, open late, and close enough to walk to. Cared for through local stewardship.

Picture independent bookstores renting books out — maybe on a subscription model. Or developers transforming defunct buildings into libraries that double as green public spaces and marketplaces.

Today’s librarians aren’t just curators — sometimes they are influencers.

We need to revive libraries as vital public infrastructure. As a means for economic and cultural access. It starts with imagination — and maybe by bringing back library cards.

* Victoria Navina is a public health professional, a researcher and the founder of Kuala Lumpur Reads, a silent reading initiative in Perdana Botanical Garden that is now a country-wide network of silent reading communities.

** This is the personal opinion of the writer or publication and does not necessarily represent the views of Malay Mail.